As per the Supreme Court of Canada in: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/17416/index.do

The mandatory victim surcharge constitutes punishment, engaging s. 12 of the Charter , and its imposition and enforcement on several of the offenders, as well as the reasonable hypothetical offender, result in cruel and unusual punishment. The surcharge cannot be saved under s. 1 of the Charter . It is not necessary to consider whether s. 7 of the Charter is infringed.

The surcharge constitutes punishment because it flows directly and automatically from conviction and s. 737(1) itself sets out that it applies “in addition to any other punishment imposed on the offender”. The surcharge also functions in substance like a fine, which is an established punishment, and it is intended to further the purpose and principles of sentencing.

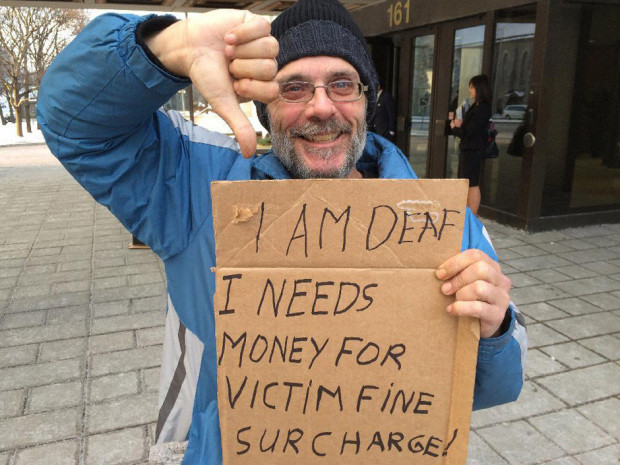

The surcharge constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and therefore violates s. 12 of the Charter , because its impact and effects create circumstances that are grossly disproportionate to what would otherwise be a fit sentence, outrage the standards of decency, and are both abhorrent and intolerable. In the circumstances of this case, the fit sentence for the offenders would not have included the surcharge, as it would have caused undue hardship given their impecuniosity. Sentencing is first and foremost an individualized exercise which balances various goals, while taking into account the particular circumstances of the offender as well as the nature and number of his or her crimes. The crucial issue is whether the offenders are able to pay, and in this case, they are not.

For the offenders in this case and for the reasonable hypothetical offender, the surcharge leads to a grossly disproportionate sentence. Although it advances the valid penal purposes of raising funds for victim support services and of increasing offenders’ accountability to both individual victims of crime and to the community generally, the surcharge causes four interrelated harms to persons like the offenders. First, it causes them to suffer deeply disproportionate financial consequences, regardless of their moral culpability. Second, it causes them to live with the threat of incarceration in two separate and compounding ways — detention before committal hearings and imprisonment if found in default. Third, the offenders may find themselves targeted by collections efforts endorsed by their province of residence. Fourth, the surcharge creates a de facto indefinite sentence for some of the offenders, because there is no foreseeable chance that they will ever be able to pay it. This ritual of repeated committal hearings, which will continue indefinitely, operates less like debt collection and more like public shaming. Indeterminate sentences are reserved for the most dangerous offenders, and imposing them in addition to an otherwise short‑term sentence flouts the fundamental principles at the very foundation of our criminal justice system.

The surcharge also fundamentally disregards proportionality in sentencing. It wrongly elevates the objective of promoting responsibility in offenders above all other sentencing principles, it ignores the fundamental principle of proportionality set out in the Criminal Code , it does not allow sentencing judges to consider mitigating factors or the sentences received by other offenders in similar circumstances, it ignores the objective of rehabilitation, and it undermines Parliament’s intention to ameliorate the serious problem of overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in prison. The cumulative charge-by-charge basis on which the surcharge is imposed increases the likelihood that it will disproportionately harm offenders who are impoverished, addicted and homeless. It will also put self-represented offenders at an additional disadvantage because they may not know that they may negotiate the terms of their plea in order to minimize the amount of the surcharge. While judicial attempts to lessen the disproportion may be salutary, they cannot insulate the surcharge from constitutional review. Indeed, reducing some other part of the sentence may minimize disproportion, but it cannot eliminate the specific and extensive harms caused by the surcharge. Moreover, imposing a nominal fine for the sole purpose of lowering the amount of the surcharge would ignore the legislature’s intent that the surcharge, in its full amount, would apply in all cases as a mandatory punishment.

It is unnecessary to engage in a s. 1 Charter analysis, because the state did not put forward any argument or evidence to justify the surcharge if found to breach Charter rights. It follows that the mandatory victim surcharge imposed by s. 737 of the Criminal Code is unconstitutional.

Section 737 of the Criminal Code should be declared to be of no force and effect immediately. The state has not met the high standard of showing that a declaration with immediate effect would pose a danger to the public or imperil the rule of law. Reading back in the judicial discretion to waive the surcharge that was abrogated in 2013 is also the wrong approach, because it is a highly intrusive remedy, and because Parliament ought to be free to consider how best to revise the imposition and enforcement of the surcharge. Because robust submissions on the issue were not made, it would be inappropriate to grant a remedy to offenders not involved in this case and those no longer in the system who cannot now challenge their sentences. However, a variety of possible remedies exist. The offenders may be able to seek relief in the courts, notably by recourse to s. 24(1) of the Charter . The government could also proceed administratively, while Parliament may act to bring a modified and Charter -compliant version of the surcharge back into the Criminal Code .